The practical problem with Save the Cat

Whatever you think of the theory, the real problem is it's a poor outlining aid

The Save the Cat books are a great way into thinking about structure, especially Save the Cat Writes a Novel, which has a breakdown of about a dozen successful modern novels. I recommend that book without hesitation, especially to younger people.

However, Save the Cat has two problems… well actually three.

Problem Zero is that you can pretty much watch a Netflix movie and predict what’s going to happen minute by minute, because a chunk of the entertainment industry seems to have glommed onto Save the Cat as a source of certainty… much like studio execs of yesteryear thought everything should be the Hero’s Journey.

However, originality of structure is probably overrated, and working to any beat sheet is a great way to finish a novel. So let’s pass over that.

Problem One is that the Save the Cat beat sheets aren’t as generalisable and therefore as bi-directional as the hype suggests. You can tell this just by reading the examples given in the StC books, where there’s a certain Procrustean shoe-horning at work to make the existing and successful story fit the StC beats and A & B Story divisions. Various online essays make a fun parlour game of this, but taxonomy isn’t process.

The StC system breaks down when applied to something as iconic as Indiana Jones or original Star Wars movies; you can make them fit, but it’s hard to imagine how you’d get from a StC beat sheet to those stories. My brain melts at the prospect of the applying this in either direction to a sprawling but tight Ken Follet thriller like Dangerous Fortune. And the nail in the coffin is that StC neither reliably describes nor generates old-fashioned but highly readable Pulp.

The best that can be said of the StC beat sheet is that it’s a highly optimised instance of the human Ur Beat Sheet, which merely comprises of an interesting string of reversals:

There’s this King who has everything, but he’s scared of mortality. He and his best friend set off on a quest for immortality, but a dragon kills his friend. The King kills the dragon, but it curses him.

Yes, the Basic Beat Sheet is basically an interesting butt-load of buts. (For anything longer than a short story, the “interesting” part is the real challenge. A good start is to think of them as “Struggle but Derail” pairs.)

So, though you can write to the StC beats successfully, and make an existing story fit them retrospectively, it’s not clear that you can take the story in your head and write it usefully via the StC beats or use them as a way into creating a story in flow.

Certainly, the more I tried it, the more it derailed me.

Problem 2 is that the Save the Cat beats aren’t a story. That makes them uninspiring to work with, and difficult to translate directly to an outline.

Don’t believe me! Go take another look at their Beat Sheet Mapper. I think it’s useful for checking your work, but it’s not linear and it doesn’t bake in the buts.

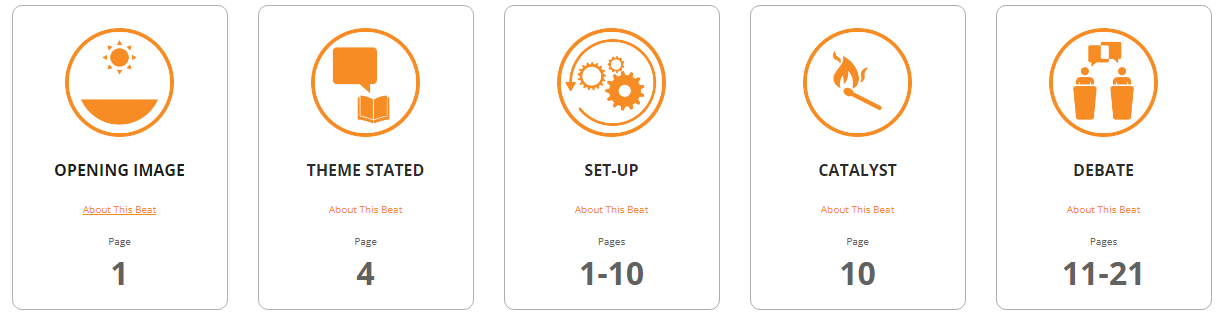

Take the first line, I screen captured up top of this article (I inputted 100 for the page count, so we get percentages):

Opening Image (1%), Theme Stated (4%), Setup (1-10%), Catalyst (10%), Debate (11-21%).

These are all good things to have in your story, but they don’t present a continuous section of a story, so much as describe it. Untangled, we get:

Setup (1-10%) but Catalyst (10%), but Debate (11-21%)… and by the way you need to put in an Opening Image at 1% and a Theme Stated moment at 4%.

That’s not remotely an outline, but rather it points to a sort of virtual outline forming in your head. So now you have two different reference documents, the optimised but non-linear StC beat sheet, plus the actual outline that perhaps just exists mentally.

Holy Cognitive Overhead Batman!

Speaking for myself, I like telling actual stories… losing myself in the rhythm of them. That’s what I love about outlining; spinning possible future books, remembering backwards. So, I find this non-linear approach uninspiring. It also makes it hard to test the emerging story against my instincts.

However, the main technical issue caused by the Save the Cat beat sheet not being a story is that it doesn’t translate to an outline. The “significant moment beats” — Opening Image, Theme Stated… are moments, not chapters. When you take them out, you get a series of Long Beat - Short Beat pairs that look something like this:

Set-Up but Catalyst (1-10%)

Debate but Break into Act 2 (11-22%)

Fun and Games including B Story but Mid Point (23-50%)

Bad Guys Close In Struggle, but Dark Night of the Soul (51-76%)

Break into 3, but Finale (77-100%)

That’s not a bad way of thinking about structure, but I think the blocks are too big to be useful for outlining.

For example, “Setup” is 10% of the novel, that’s perhaps 10,000 words that have to be twisty-turny and interesting in their own right. Worse, it makes it hard to address the way that some storylines or arcs will bracket the division between these — for example, in Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nepal sequence kicks off during StC’s “Debate” and ends some of the way into “Fun and Games”— but I talked about that in my last article.

So, yes, read the Save the Cat books to learn good strategies to make your stories work, and to have access to invaluable structural summaries of successful films and books. Use the Save the Cat beat sheets if they fit the kind of story you’re telling, especially if you are just starting out. However, for the actual work of creative outlining, use a word processor, or the Scrivener corkboard I talked about in my previous article.

I don’t really have anything new to sell off the back of this, but you can see my books on Amazon here. You can also…

This is so true. I don't mind playing with STC as a way to make some sense of my outline, but I find it nearly impossible to use as a starting point. I have to have the map, first, to know where I'm going.